I don’t update this blog very often anymore, but I share weekly updates about the process of writing my memoir in my Substack newsletter. Check it out!

I just returned home from celebrating the fortieth birthday of one of my first blog friends, Ali Feller of Ali on the Run, so what better way to memorialize the occasion than with an old-school blog recap?

Two weeks ago, I was walking my dogs while listening to Ali’s podcast recap of Boston Marathon weekend when I realized her milestone birthday was coming up. “I’ll have to remember to send her a card,” I thought.

When I got home and checked my email, one of the subject lines gave me a jump-scare: “Re: Feller Forty – You’re Invited!”

I’m sorry, what? The message was a last call to RSVP for Ali’s birthday celebration, but I hadn’t gotten the first call! All of a sudden, I was sweaty, panicked. How had I missed the initial message? Was it too late for me to figure out how to get to Hopkinton, New Hampshire, the following weekend?

I found the original invitation buried in my junk folder (thanks for nothing, Gmail!) and got up to speed on all the details. I checked out flight costs, ran it by Aaron, shot Ali a text, and before I knew it, I was booked on a flight to Boston.

My friendship with Ali started in her email inbox. After I started running and blogging in 2010, I found her blog and began following along as she trained for her first marathon. When I planned a trip to New York City in 2011, I was training for my first marathon and had a long run to do while I was in town. Ali didn’t have any clue who I was at the time, but I emailed her to see if she’d be interested in running with me. She replied with a nice message saying that she’d love to, but she’d be out of town. From there, we stayed in touch and finally got the chance to run together when I visited NYC again in March 2015.

I was training for the Big Sur International Marathon and had 19 miles to run. Ali joined me for the first 13 miles, slipping and sliding along the slushy sidewalks of Manhattan and her favorite Central Park paths. As all runners can attest, there’s no better way to get to know someone quickly than while running. Something about sweating side-by-side together makes it easy to go deep.

At the time, I was 27 and Ali was 29. I had just gotten married and was going to try to get pregnant after Big Sur. She was planning her wedding. It was a pivotal time of big changes on the horizon for both of us.

Since then, there’s been a wedding and babies. A new job for me, a new podcast for her, and more marathons for both of us. An Alzheimer’s diagnosis and a cancer diagnosis. Unspeakable grief and heartache in many forms. We’ve cheered for each other and cried for each other from opposite coasts for more than a decade.

When Ali was going through cancer treatment, I let her know I’d be there in a heartbeat to help with chemo or cold capping or whatever she needed, but because everyone loves her, she had that offer from a lot of people. I didn’t get the chance to support her in person at her lowest, but now I had the chance to celebrate her as she enters a new decade, the very beginning of an era in which I’m certain she’ll be at her highest. I wouldn’t miss it for the world.

I was excited, too, to visit Boston for the first time, just a few weeks after this year’s Boston Marathon, where my friends Beth and Kerri crushed the race and reignited my desire to qualify for it someday.

I got into town on Thursday evening and dug straight into a hot, buttery lobster roll made with a perfectly soft and chewy brioche bun at Saltie Girl. On Friday morning, I did a little running tour of Back Bay and snapped photos of all the sights runners dream of: the Charles River; the giant CITGO sign that signals the end of the marathon is near; the corner of Hereford and Boylston; and the Boston Marathon finish line, which is permanently painted on Boylston Street. The weather was gray and drizzly, so I didn’t get to see the city in its full glory, but it was perfect for a contemplative solo run fueled by big dreams.

After I showered and had lunch, it was time to pick up my road-trip crew. Ali’s friend Conor Nickel, who used to plan massive events for New York Road Runners, was in charge of planning the festivities, and he asked if I could drive his boyfriend, Zach Cole, and best friend, Jess Movold, from Boston to New Hampshire. I was nervous because I didn’t know anyone attending the party besides Ali, so it was nice to be able to get to know a few of her friends on the drive instead of showing up at her house all by myself. I figured any friend of Ali’s is a friend of mine, and that proved to be the case time and time again throughout the weekend.

We rolled into downtown Concord, New Hampshire—all quaint red brick, ripped straight from a Netflix Christmas movie—to pick up coffee and food, then proceeded along winding country roads to Ali’s house.

Ali answered the door wearing glittery undereye patches, which couldn’t be more her. The vibe was relaxed as we ate and chatted with Conor, Ali’s Cousin Jackie (most certainly her legal name by now), and Cousin Jackie’s husband, Neil. Neil and I somehow went deep into hard-hitting life topics within five minutes of saying hello, and we weren’t even running! I guess that also happens when people are open and easy to talk to.

The first event of the weekend was a welcome party at the Contoocook Cider tasting room at Gould Hill Farm. As we all got ready, I answered the call to help curl Ali’s hair and gave her my signature waves with a flat iron. Ali has been open about struggling with losing a lot of her hair due to chemo, and she’s now working with a mix of her previous hair, new growth, and extensions. I was honored to be entrusted to help style it. She looked beautiful!

The welcome party was cozy and casual. Friends and family filtered in throughout the evening, and it was fun to chat with people from so many facets of Ali’s life. Girl’s got a lot of friends! I got to know her father, David; her ski-team friend, Tom; her sister-in-law, Michaela; her college friends, Dana and Teddy; and more. We munched on pretzel bites, pizza, and brownies, and the cider was flowing for the drinkers. At one point, Mary Wittenberg (former CEO of New York Road Runners and race director of the New York City Marathon) played a video of TikTok dance that looked complicated to me, but Ali picked it up right away. Once a dancer, always a dancer.

After the welcome party wound down, we headed back to Ali’s house to continue hanging out. I had a lovely chat with pro runner Keira D’Amato, who is Ali’s close friend and the American women’s record holder in the half marathon. She told me all about her book that’s coming out in September and asked me about my book! (I’ll share more about our convo in my next Substack update.)

Conor rallied a group of people to do an 8:15 Orangetheory class in Concord the next morning before a planned run, and my FOMO eventually convinced me to sign up as well. I may or may not have forced Cousin Jackie to join, too.

I was lucky enough to stay over at Ali’s house, along with several other friends, and I got to sleep in her office, where she records her podcast episodes! I’ve been on Ali’s show a few times (first as a guest, then as a guest host), and it was fun to be in the room where it all happens.

Saturday morning, I was up early to do my pre-run knee taping, foam rolling, and stretching in Ali’s basement workout room. Zach and I headed to Concord early to grab coffee and food, since I’m always immediately starving when I wake up and need a solid breakfast in my stomach before I work out.

The Orangetheory class was great! The more experienced Orangetheory folks didn’t love some parts of it, but as a first-timer, I had fun and got a decent workout. There were eight of us, and we all started on the rowers and strength, then moved to treadmills for the second half of the class. The class flew by and I got pretty sweaty. Some of us were smart and brought clean clothes to change into for the run; I was not part of that group. 🤣

After class, as we got ready to leave, I noticed Mary Wittenberg had a banana and asked her if she thought the Starbucks across the parking lot might have bananas because that sounded so good at the moment. She said she only wanted one bite of hers and insisted on giving me the rest, which was so nice of her and really hit the spot!

Next, we headed to Memorial Field for the run. There was a bit of confusion as to whether it was a race or a fun run, but the official name was “Ali Feller’s Ali on the Run Show Contoocook Meredith Palmer Memorial Celebrity Rabies Awareness Pro-AM Fun Run Race for the Cure 4.0-Mile Run,” and we ultimately decided it was a race.

Keira, who ran from Ali’s house as part of a 15-mile run and met us in the parking lot, offered Cousin Jackie a significant head start, and I jumped in on that. Jackie wasn’t feeling so great after doing squats at Orangetheory and a bunch of hiking earlier in the week, so I vowed to stick with her and run, walk, or whatever she wanted to do to get to the finish. I had no desire to race Keira or any of the other super-fast people in the group, for that matter. 🤣

It was pouring rain and in the 50s, but I was nice and warm from Orangetheory and I’m super used to this weather in Seattle. Even though we got completely soaked, we all looked so cute decked out in our pink Taylor Swift-inspired shirts and “ball sports fan” hats to celebrate Ali.

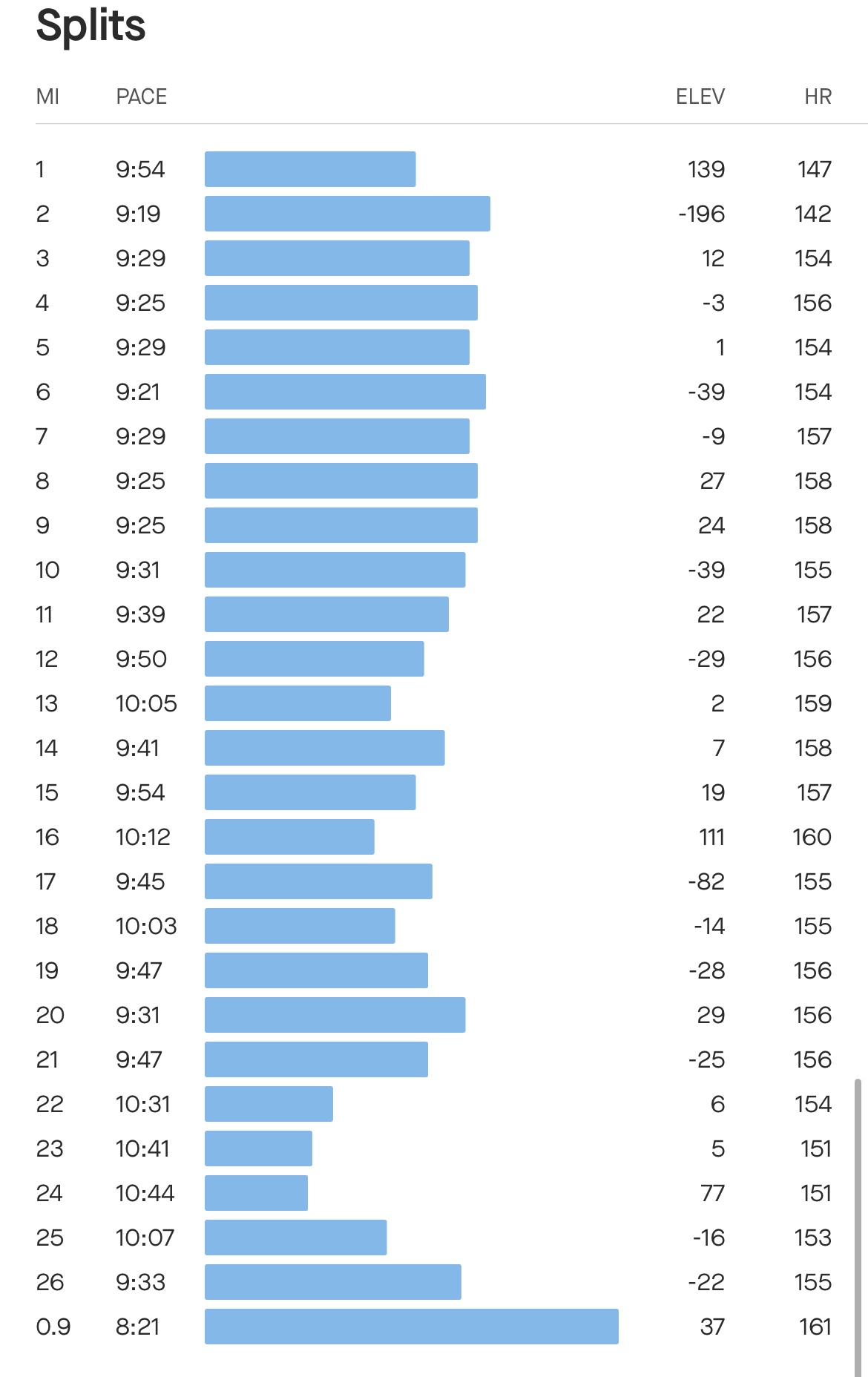

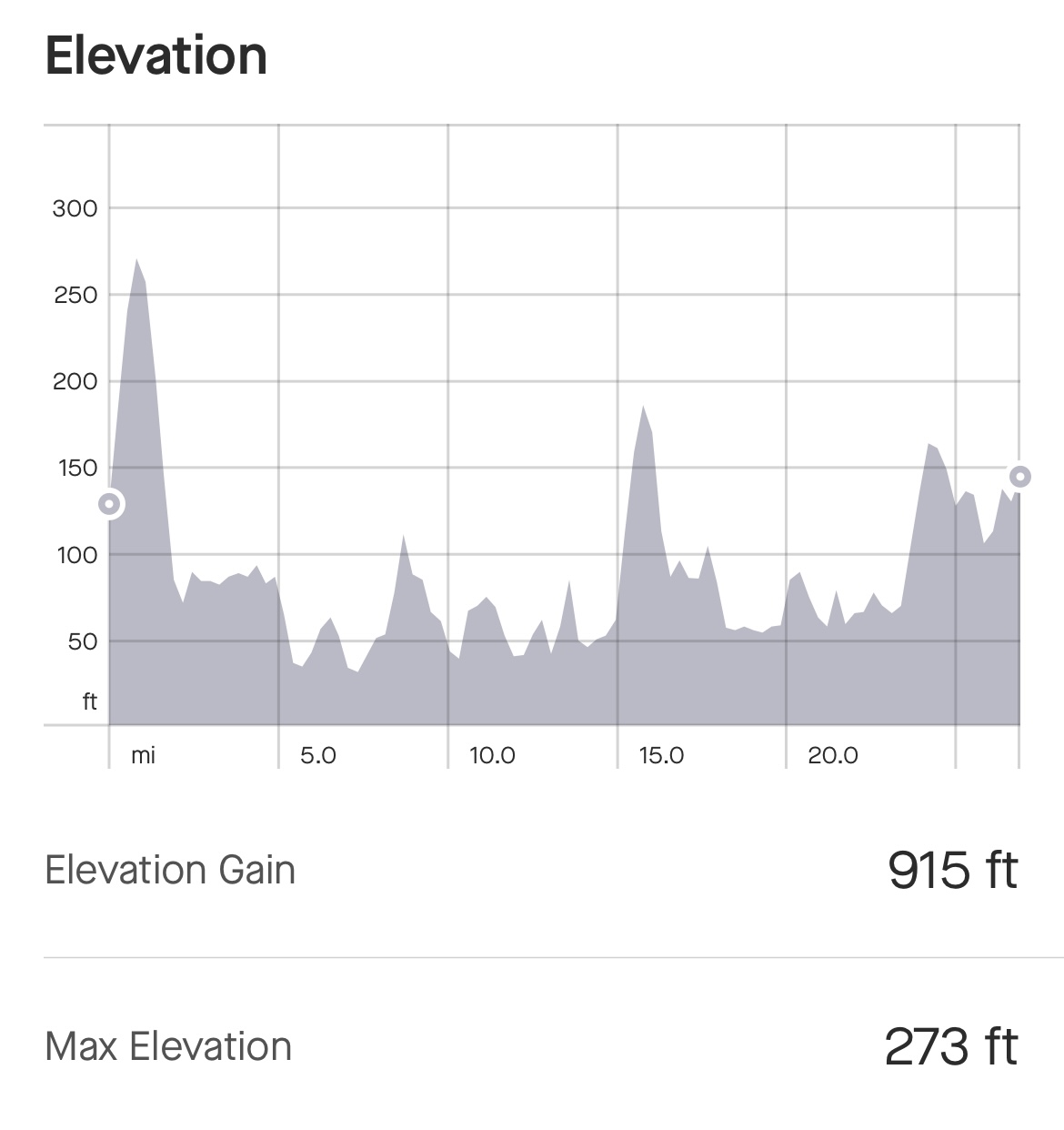

Cousin Jackie and I took off first. We were promised a 14-minute head start, but in reality, we got two minutes. It only took Keira, Conor, and Zach about three minutes to catch up, but we had fun heckling them as they smoked us. We eventually got passed by everyone and took our time with frequent walk breaks. I felt terrible that Jackie was in pain, but she gutted it out like a champ! We finished with a very respectable 9:38 average pace, so we must have been hauling while we were running. The group formed a cheer tunnel for us to run through as we finished, which was so fun and indicative of the supportive, celebratory spirit of the whole weekend.

Then Zach and I hightailed it back to Ali’s house while she and handful of friends picked up açaí bowls for everyone from Playa Bowls. I was the last to finish the race, but the first to get a warm shower, so who was the real winner??

The Nutella açaí bowl they got for me was not only the first açaí bowl I’ve ever had, but one of the greatest things I’ve ever tasted. Maybe it was due to my exhaustion after the back-to-back Orangetheory class and run; or the whiplash of going from being wet and cold to warm and cozy; or the irresistible combination of the creamy açaí base, crunchy granola, gooey Nutella, and juicy fresh fruit. In any case, I’m pissed we don’t have Playa Bowls in Seattle, and I’ll spend the rest of my life trying to find or recreate an açaí bowl as good as that one.

Once we were all fed and showered, it was time to prep Ali’s house for the party. A creative group got to work on the decorations while I snuck upstairs to dry my hair and put on makeup (I had the limited bathroom space on my mind and wanted to get it out of the way). Then I helped with food and drink prep, plus setting up plates, utensils, and such. Assembling two charcuterie boards was my crowning achievement. I’m no Martha Stewart, but I did my best!

Ali rounded everyone up to give a toast before the rest of the guests arrived. She started crying almost immediately as she expressed such heartfelt gratitude for everyone coming to celebrate with her. Between cancer treatment and a divorce, she’s been through more these last two years than any one person should have to handle.

I didn’t cry until she started talking about laundry. I’ll pull from the story she shared on Instagram, since I certainly can’t say it any better:

Divorce with a young kid is really hard. There’s no denying that. For me, it was the unexpected little moments that were sneaky, unconsolably hard.

Doing Annie’s laundry has always been one of my favorite things. Since before she was born, there’s always been something so sweet and comforting about washing and folding those tiny socks and onesies, and now the twirly dresses and flare pants.

So the first time I did laundry and none of it was Annie’s because she was at her dad’s, I broke down. Heavy sobs on the bathroom floor. I was broken. I was sad and alone and scared, and I missed her so much that I thought my heart might be physically broken.

Fast forward a bit, and I still hate the loads without the little socks. But sometimes in that sadness, you find something beautiful.

This weekend, as party prep was in full swing, I sat on the bathroom floor moving the laundry from the washer to the dryer.

A big load of laundry! Post-rainy run laundry.

It was mine.

And Cousin Jackie’s.

And Jess’s.

It was Keira’s and Devon’s and Zach’s and Conor’s and Neil’s.

It was a full load of laundry.

It went perfectly with my very full heart.

That heart had broken. And then all these people—and especially Annie—put it back together again.

All Ali wanted for her birthday was to fill her house with love, and that’s exactly what happened. The sparkly decorations and the massive spread of food and the big-name guests were great, sure, but it was a bunch of smelly running clothes soaked with rain and sweat that meant the most. It was the intimacy and togetherness, the result of sticking by each other even when things got tough and messy. It was incredibly inspiring, and my heart felt full, too—on behalf of Ali, and because of Ali.

We went around the room sharing little tributes to Ali, but guests starting arriving before I got the chance to say something, so I’ll share what I was going to say here.

Ali is one of those people who makes you feel like you’re the most special person in the world when you talk to her. She naturally shines as a person, but always makes sure to turn her spotlight on others and highlight the best in them. When she first asked me to be a guest on her podcast, I was shocked because I didn’t think anyone would care about my story as a very average runner, especially compared to the professional runners and legitimately popular bloggers she’s had on her show. But she convinced me I mattered, and empowered me to share the story of my mother’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis for the first time. It was only then that I realized I had a lot to say about it. Right after our conversation, I felt inspired to start writing about my mother’s journey, which has since snowballed into lots of writing over the years, and now the full-time pursuit of sharing my mother’s story in a memoir. Maybe I would have ended up here anyway; maybe I wouldn’t have. But Ali was unwittingly the catalyst, all because of her huge heart and genuine interest in others.

Ali has said that her friends have kept her alive over the past few years. They’ve sat with her during chemo, answered dark and scary phone calls, and helped pick her up off the floor on numerous occasions. But Ali built this incredible support network for herself by turning strangers into friends everywhere she goes—from the ski team to the cancer center, from major marathon finish lines to random corners of the internet.

You may give all the credit to your friends, Ali, but there’s a reason they’re all there for you in the first place. You did that.

It was a beautiful, inspiring thing to see Ali’s support network in person, and I know this is just a fraction of it!

I chatted with a bunch of different people during the party, but had to take a little break to breathe after every three or four conversations. I’m an extroverted introvert, so I can easily turn on the outgoing part of my personality in social situations, but can also feel drained and need to recharge every now and then. I’d sneak upstairs to my room/Ali’s office just to have a few quiet moments before returning to meet more people. I marvel at Ali and many of her friends who seem to have endless energy to chat all day!

I had especially great conversations with Ali’s dad, who promised to give me a tour of New Hampshire’s best covered bridges should I ever return, and another one of Ali’s friends (not Keira) who just got a book deal. The deal hasn’t been announced yet, so I’ll keep the person’s identity under wraps, but I’ll share some interesting tips they gave me about the publishing world in my next Substack update.

Can we talk about the incredible cake Ali’s friend Aubree made?? It was so beautiful, on theme, and delicious. Usually fancy cakes look way better than they taste, but this chocolate creation was perfectly moist and had the ideal cake-to-frosting ratio. Five stars, chef’s kiss, no notes.

I loved the happy look on Ali’s face as she contemplated her birthday wish. There are so many good things ahead for her, and she deserves them all.

The weather had been rainy my entire time in New Hampshire, but finally cleared up on Saturday evening. Zach, Greg Laraia, and I took a little break from the party to drive back to Gould Hill Farm to see the beautiful view we’d missed on Friday night, and to check out a covered bridge. Lovely!

The party went well into the night, then wound back down to the core group that was staying at the house. That chill, sweatpants hangout time was among the most fun, even though I felt like I was quieter than most, given the limited capacity of my social battery. I was just happy to be there!

After helping clean up and saying my goodbyes to everyone past midnight, I was up at 5:30 on Sunday morning to hit the road back to Boston and catch my flight home. I didn’t get a lot of sleep over the weekend, but all the fun was well worth it. I’m so glad I could play a (very small) part in making the weekend special for Ali.

I took away so many lessons from the experience:

Friendship comes in many forms. Embrace them all.

Surround yourself with people who’ll be there for you in the best and worst of times.

Tell those people you love them, early and often.

You can find joy in anything, even laundry.

Celebrate everything enthusiastically and unabashedly, especially birthdays.

And at forty, life’s just getting started.